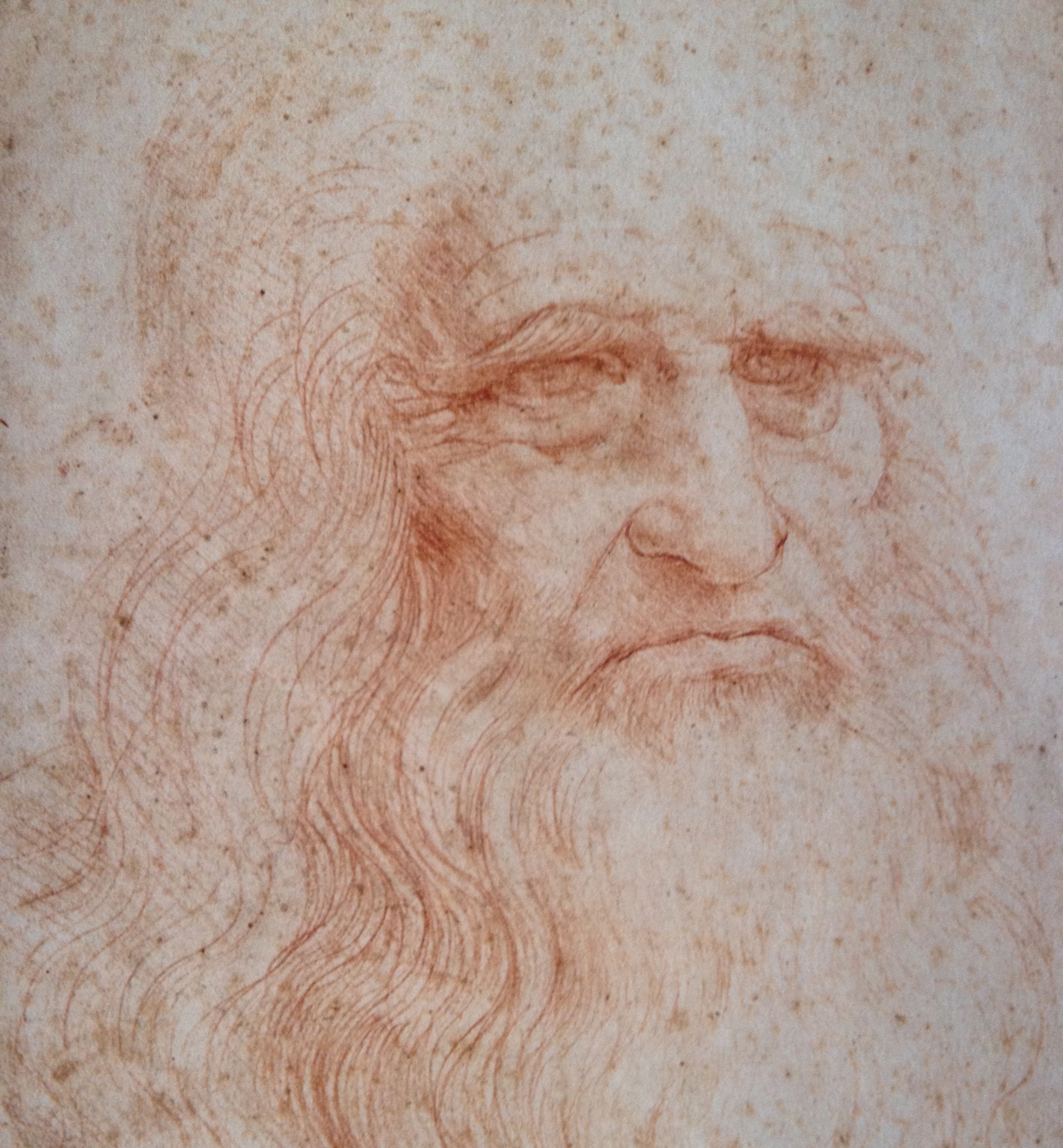

Notes on Leonardo da Vinci

A Twenty Year Restoration

(Image- Christ prior to latest restoration 1977-1999)

According to recent studies, although discontinuously, Leonardo da Vinci started working on the Last Supper in 1492 and completed it in early 1498. It was indeed an ambitious project conducted with an experimental technique that failed to resist and within 20 years the painting was already showing signs of deterioration. Nonetheless it seems quite amazing that the latest of at least 11 restoration campaigns has spanned slightly more than two decades (1977 – 1999).

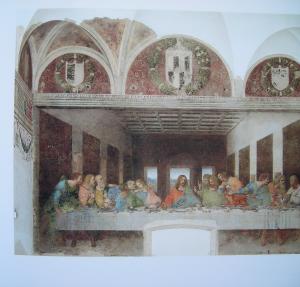

Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper

(Image - View of Leonardo's Last Supper)

The commemoration of Jesus’s farewell meal with his twelve disciples, known as The Last Supper, or Cenacolo, is amongst the most widely represented subjects in the history of Christian Art closely related to the institution of the sacrament of the Eucharist, re-enacted every time a Holy Mass is celebrated.

But before Leonardo’s masterpiece was carried out artists seemed to be more interested in the religious aspect of the Last Supper rather than in the investigation of human feelings that follows the announcement of Jesus’ imminent betrayal by one of them.

The Last Supper execution at St. Maria delle Grazie took a few years because of Leonardo’s erratic methods. Painted on a wall with a medium based on egg and oil that unlike the fresco technique proved its frailty almost from the start, the Last Supper was hailed as a masterpiece since it’s appearance and held in the greatest veneration not only by the local artistic milleu but by artists and erudites from all over Europe.

Today if we can argue that the choice of a mural support and the inadequate tempera technique resulted in the immediate and irreversible deterioration of Leonardo’s Last Supper, conversely we can claim that the same reasons thwarted whatever attempt to strip the masterpiece from its original premises and relocate it elsewhere.

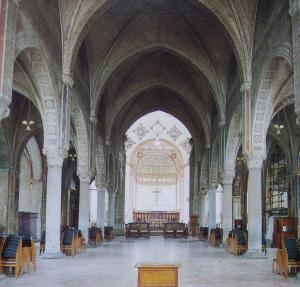

The Church of St. Maria delle Grazie

(Image - Interior view of St. Maria delle Grazie)

The Church of St. Maria delle Grazie was built on the north western border of Milan for the Dominican Orthodox order. The land was generously endowed by Gaspare Vimercati, a nobleman connected to the ruling dynasty, a military commander himself like Duke Francesco Sforza.

Planned in plain Lombard Gothic style by architect Guiniforte Solari, the church was built starting from 1466 and completed within a couple of decades. Towards the end of the 1490’s following the replacement of Guiniforte Solari by Donato Bramante, an outsider architect who came from Urbino, in the Marches, the Church underwent expensive and extensive reconstruction works to meet the requirements of Ludovico Sforza, now Duke of the Milanese State.

Part of the extant church was demolished and a true gem of Renaissance Art replaced the transept. A new concept of space and light was introduced and the overwhelming decorations of the Gothic style cruxific form Church gave way to a building, the Tribune, allusive of celestial harmony and charged with esoteric symbolism.

Completed in 1497 to allow, the burial of Ludovico’s young spouse, Beatrice d’Este, who died prematurely in childbirth on the 2nd of January of the same year, Bramante’s Tribune was completed with a beautiful choir in inlaid wood that provided a warm embrace to the marble tombstone carved by Cristoforo Solari that featured the ducal couple lying together in death.

Partly damage during the Word War II bombardments although not as severely as the Refectory that houses Leonardo's Last Supper, the Church was restored in the late 1940’s and more recently in the 1990’s.